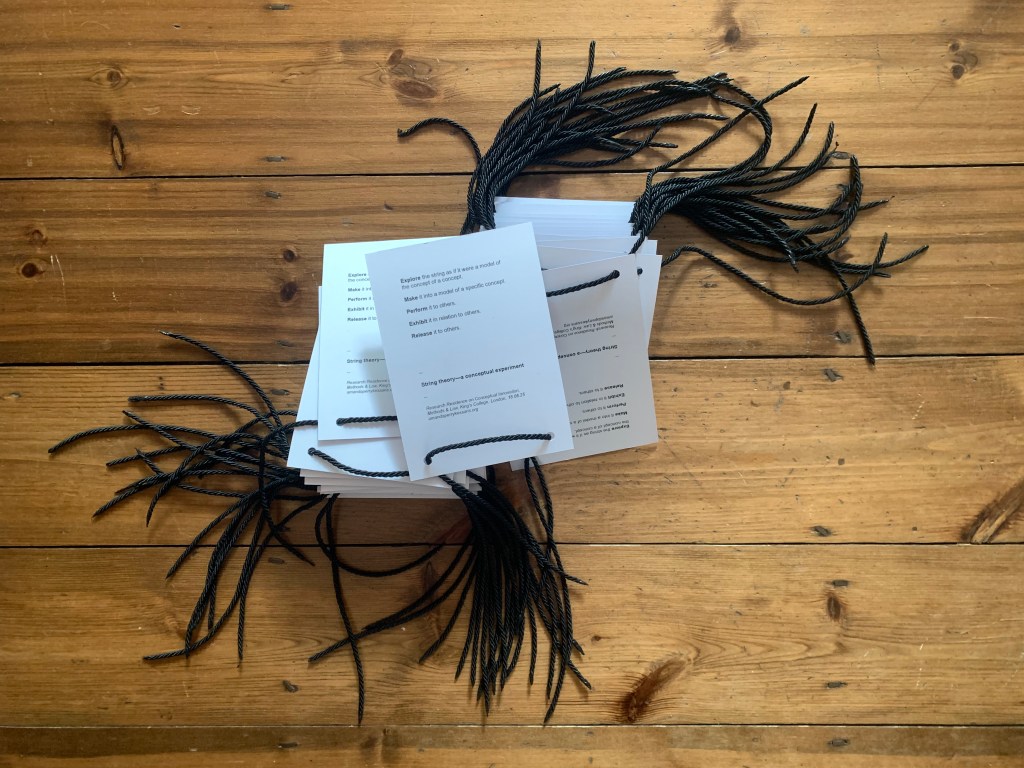

Figure 1: Toolkit for String theory-a conceptual experiment (c) Amanda Perry-Kessaris 2025.

This post introduces an experiment that I designed for as part of a Summer Research Residence on Conceptual Innovation, Methods & Law organised by Davina Cooper at Dickson Poon School of Law, King’s College London in 2025.

For theoretical physicists, ‘string theory‘ is the idea that the universe is made up not of dot-shaped atoms (or electrons or quarks), but of vibrating, twisting, folding, strings; and that it is the actions of, and interactions between, these strings that shape our worlds. I am not a physicist. I am (ab)using this idea as a label because it gets at certain aspects of conceptualisation that I am trying to make visible, and to activate, through the experiment.

In the Sociolegal Model-Making project (2017) I identified three types of model-making that can be useful for those working with legal ideas:

- Modular: using pre-fabricated building systems such as lego to make models of concepts or theories (particularly useful for practical purpose of explaining a concept).

- Found: taking existing artefacts that we come across in our everyday lives (such as string) or in curated spaces such as a museums and reinterpreting them as models (particularly useful for critiquing a concept).

- Bespoke: using malleable materials such as clay (or string) to make models from scratch (particularly useful for imagining a new concept or reimagining an existing concept).

The String Theory experiment detailed below is an invitation to use a length of string and a piece of paper to engage first in ‘found’ and then in ‘bespoke’ model-making; and then to use the bespoke model to engage with others around a particular concept of your choosing.

Experiment

Materials:

- 50 cm of thick black string

- blank sheet of A6 card (or an A4 sheet of paper folded once horizontally and once vertically).

Step 1: Explore your string as a ‘found’ model of the concept of a ‘concept’

- Note: material, structure, colour, texture, scent, sound, taste…

- Consider: What aspects of your understanding of the concept of a concept are/not captured in a piece of string? Does this process change your understanding of the concept of a concept? Does this process make you feel differently than traditional abstract conceptualisation? What other found artefact might you use to model the concept of a concept?

Step 2: Make your string into a ‘bespoke’ model of a particular concept

- Note: shape, (in)stability, modifications…

- Consider: What is your primary purpose in making your model (practical, critical, imaginative)? (Again) what aspects of your understanding of your concept are/not captured in your model? Does this process change your understanding of your concept? How do you feel when making the model? What does this process reveal to you about the (traditional) process of conceptualisation? What other found artefact might you use to model your concept?

Step 3: Perform your concept to others

- Note: word, movement, accessibility, participation…

- Consider: What is lost/gained through (public) performance versus (private) making? Does this process change your understanding of/feelings about your concept and/or of conceptualisation?

Step 4: Exhibit your concept in relation to others (place it on the back of your card with a caption, in a grid with other concepts)

- Consider: caption (lay, academic, practitioner), placement, discoverability, accessibility, preservation, responsibility

- Note: What is lost/gained through exhibition versus performance? What is gained/lost by captioning? Does this process change your understanding of/feelings about your concept and/or of conceptualisation? Of its relationship to/ effect on other concepts?

Release your concept to others (e.g. circulate a photograph)

- Consider: use, adaptation, damage, loss, rediscovery, oblivion

- Note: What is gained/lost when we proactively release a concept to others?

Outcomes and reflections

Below are examples of outcomes and reflections generated by this experiment. If you complete the experiment and wish to share your outcome and reflections with me and/or the wider world do please get in touch via email.

Aman

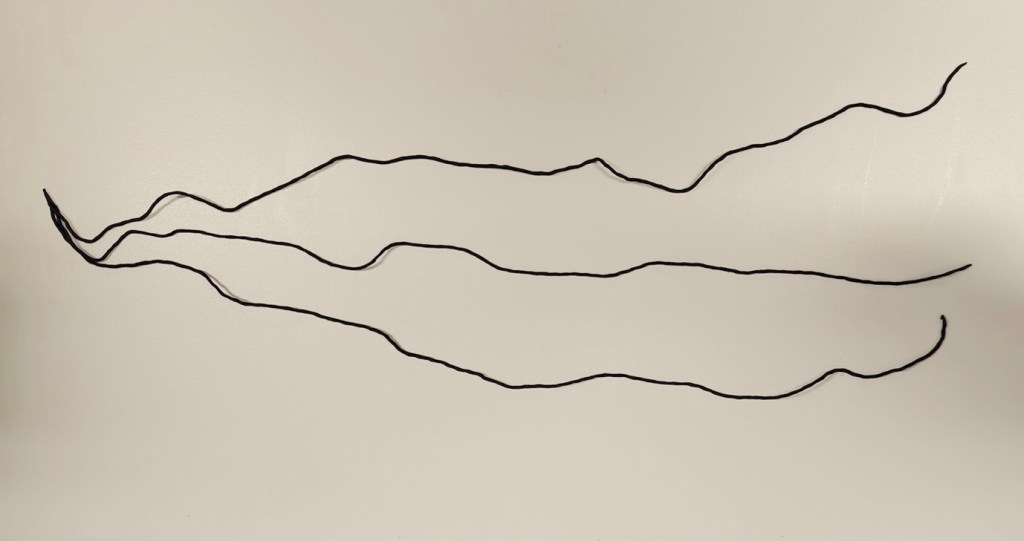

I was drawn to the neat entanglement of the “String”. Using the String with a capital ‘S’ for the 50 cm of black string that the experiment began with. One of the ends offered the easy possibility of disentangling the three strands of the String and I was excited by the possibility of such unmaking. Having been proximately involved in thinking about idea how law (international law in particular) limits the way international law allows the experience of “freedom” for movements that are demanding self-determination, and working with accounts that attempt to resist/find way around such limits – I quickly arrived at the idea of how “disentanglement” was to be my attempt to depict that experience of freedom. I had imagined that I would be successful in separating the three strands (or ‘strings’ with a small s) that made the “String”, and perhaps in consonance with a limited creative impulse attached to my imagination with such making (or unmaking), I decided that the resultant ‘bespoke’ model could depict such freedom. Fearing that the end would snap, I ended up with the image attached as the final model.

I am not sure of the value of the release of such a model, but the making (or the unmaking) of the string raised several questions for me. One, I was drawn to methodological choice of “disentanglement” for modelling – or calling such model “freedom”. I know why I disentangled the String, but I was more curious about why I was quick to call it “freedom.” Two, I was also curious of why I stopped with the fear of snapping. I may have ended with three unequal strands of the string – would that have been less of a depiction? This itself could be used to tell another story besides the one on the methodological limits of disentanglement as a chosen method. This curiosity led to what could such “freedom” be if I were to be the author of such modelling. Of course, the String itself (in its disentangled form) had a huge part in generating questions. Afterall, it did offer an extra resistance to disentanglement at one of the ends (as the picture depicts), and the ‘kinks’ (possibly residue of the tensions attached to the entwining of the String when being made of the 3 strings and persisting as the String for a while) didn’t disappear on the disentanglement. I was left wondering if disentanglement as a representation for freedom was at all possible or attainable? And coming back to me – was there an expectation of a ‘perfect’ ‘originary’ freedom (in attaining ‘straight’ strings on disentanglement) that was ‘kink’ free (i.e. free from all effects of entanglement and the persistence of entanglement).

Image 1: String theory experiment outcome, Aman, 2025.

André Nunes Chaib

My idea was: what do I do with this? I have two (short) strings here. They are linked to a piece of paper. So to me, interestingly, I thought I will go for something simple. And the first thing that appeared ‘simple’ in my head was a ‘knot’. I did ask myself how can a ‘knot’ be anything simple, but ultimately when two strings appeared like that to me, it was just all too ‘obvious’ (and I know it shouldn’t be, it just seemed to me) that the one thing I had to do was bring them together. This kept me thinking for a while! And here is what I did with it (don’t mind the paper being dirty, please, I had some food opening up in my bag and it was a huge mess!!!)

When I look back at how the exercise made me think (and feel) about concepts, I have to say that I perhaps departed from the assumption that there were already concepts with which I had to ‘play.’ Those were for me the concept of a string and of a knot. I did reflect on whether the concept of a string inherently connected with ‘knots’ and if one concept could eventually become dependent or ‘glued’ to another. At the end, I realized they were not and they were independent. But it did make me think about how concepts navigate a space where there are other concepts and whether this space couldn’t be what we call the ‘concept of a concept’. How do different concepts navigate this space, colliding, glueing, following each other, etc. Anyway, these were some thoughts I had when ‘playing’ with the exercise!

Image 2: String theory experiment outcome, André Nunes Chaib, 2025.

Bhumika Billa

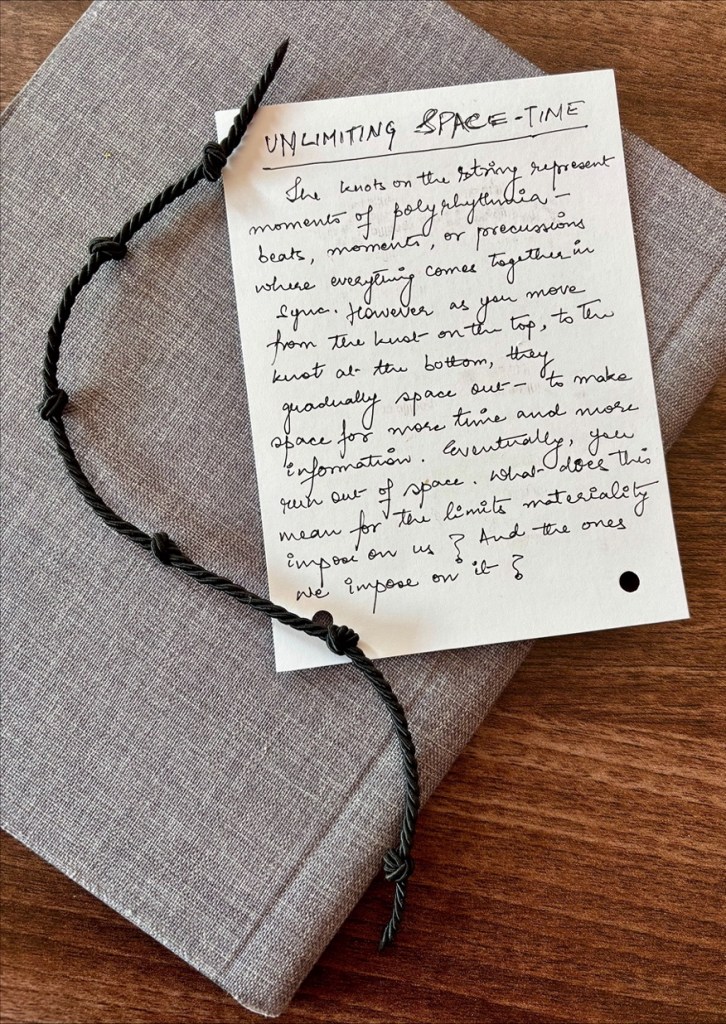

Unlimiting space-time

The knots on the string represent moments of polyrhythmia—beats, moments, or percussions where everything comes together in synch. However, as you move from the knot on the top, to the knot on the bottom, they gradually space out—to make space for more time and more information. Eventually, you run out of space. What does this mean for the limits materiality imposes on us? And the ones we impose on it?

Image 3: String theory experiment outcome, Bhumika Billa, 2025.

Clara Lopez Rodriguez

During your presentation I kept re-reading the card and instructions. I had to leave before the workshop ended and, on my commute back home, I kept (over)thinking about the card, the instructions and the string. What concept would I choose? Was I getting the instructions right? Who could I perform the concept of a concept to? The evening routine got in the way, and I forgot about the string and the card, which I had kept as a bookmarker on my desk. The next morning my (almost) 2-year-old appeared triumphant with the string in his hand—he loves to play around my books and papers. At first, he was moving the string through the air saying something like ‘brum brum’. The string now represented play, perhaps a car or a plane. Then the string fell into my bedside table and took the form of an S. I picked it up and showed it to him saying ‘shhhhhh’. He was laughing out loud; the string was still used for play, [now] representing a snake. Then I started to poke him gently with the string-snake. He laughed at first but then got really upset, took the string from my hands, and threw it to the floor. He began to cry inconsolable. The string was no longer a string, it was no longer play, it was a real snake. Happily, I was there to offer reassurance. I [no] longer know where the string-snake is because it disappeared (perhaps, thrown into the bin by a very upset but determined toddler).

I do not know if this story of the string will help your project, but it did make me think. First how not to overthink things, and how sometimes innocence or lack of prejudices can help one take meaningful action. I also reflected on the concept of performativity which I am researching in the realm of economic theory. Concepts are out there but they enact reality and have tangible effects (in this case tears and fear).

Davina Cooper

‘I thought it was a great experimental device… and it is sitting on my desk as the first thing I see when I open up my computer each morning…. it makes me smile but I’m not good at doing/ developing ideas sculpturally. So it sits as an under-utilised prompt.’

Lorna Cameron

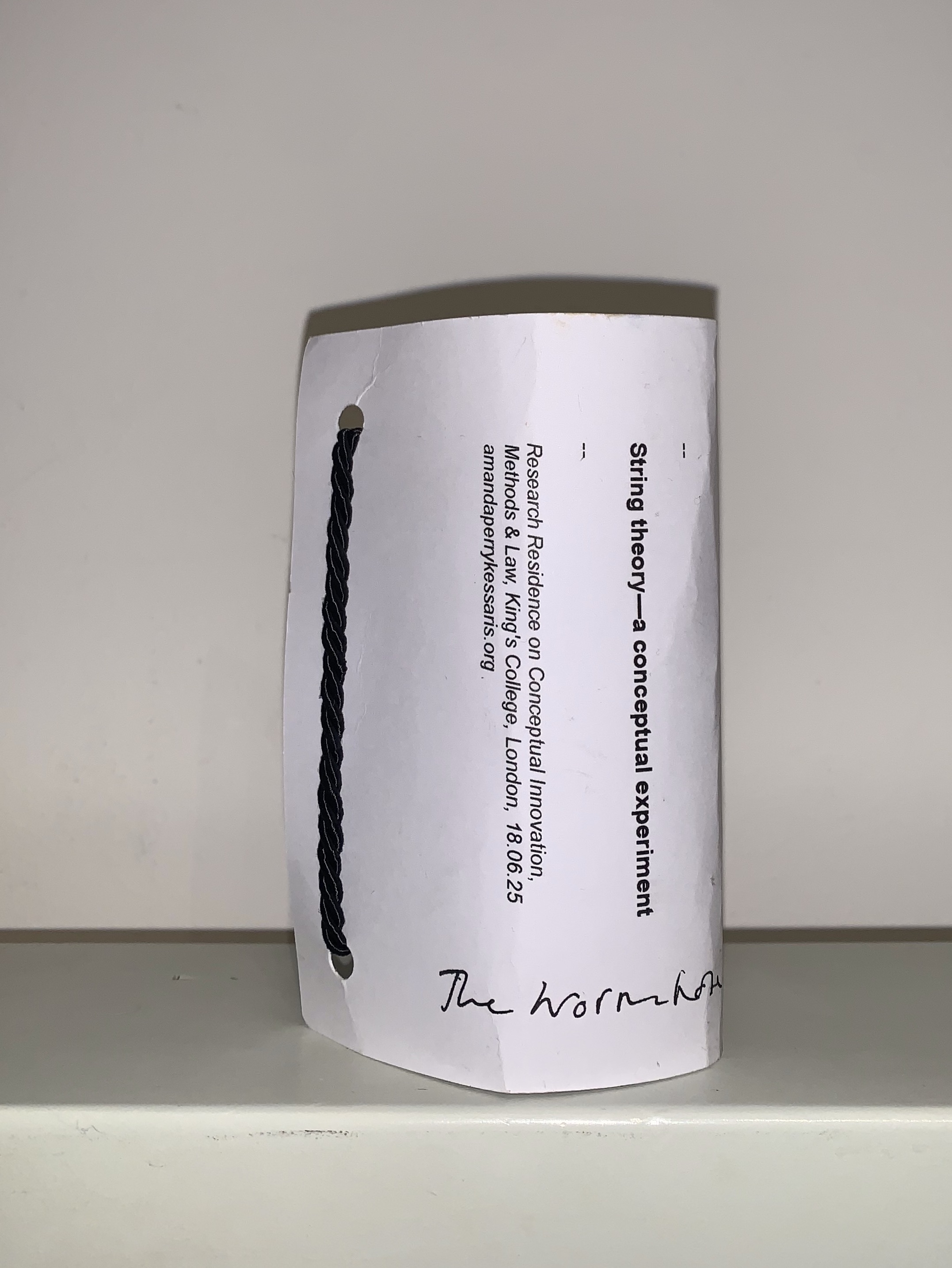

I really enjoyed this exercise in finding, and engaging with Amanda’s concept model. I found that the for me it was the interplay between the string, the card and the play on words in the name “string-theory” that allowed a creative response. The wormhole, as a tunnel joining two distant points in the universe, is created by curving space in on itself to bring those two points closer enough together to be joined by a tunnel. Hence my concept design bends the card using the string to hold the two edges together, creating a model of space-time … maybe?!

Image 4: String theory experiment outcome, Lorna Cameron, 2025.

Find out more

What designerly ways can do for legal theory:

- Amanda Perry-Kessaris (2021) Doing sociolegal research in design mode Routledge.

- Amanda Perry-Kessaris (2023) ‘Unlimiting legal conceptualisation in designerly ways’, prepared for Edinburgh Centre for Legal Theory Seminar, 16 November 2023. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4621423

Other recent examples of designerly experiments with law:

- Edinburgh Legal Theory Bazaar (2023)

- Fantasy Legal Exhibitions (2023)

- Bristol Legal Futures (2024).

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to everyone who has engaged with this experiment, to those who have shared their outcomes and reflections with me, and to those who have allowed me to share their outcomes and reflections here.